Tortuous Taxonomy, Sensuous World

As someone who just assumed that scientific names were authoritative and fixed and trustworthy, and — therefore — not very interesting, I am surely one of the readers Carol Kaesuk Yoon was addressing in writing the book Naming Nature: The Clash between Instinct and Science. She has changed my mind about many things — about the naming of nature, the nature of naming and about the nature of language itself. I had some quibbles: the text was repetitive, and sometimes a little condescending: a reader attracted to the book in the first place is unlikely to be completely ignorant of plants, animals, or Latin nomenclature, or to be one of those for whom the natural world has become almost completely inaccessible. This doesn’t diminish the achievement, however: she has been able to intelligibly layer histories of multiple sciences — botany, zoology, microbiology, anthropology, and even better, to do it without losing track of a fundamentally human, aesthetic, sensual understanding of nature.

The story is set against the background of the umwelt, a word plucked from German, where it really does mean what environment means in English. It’s been repurposed here to effectively contrast with “environment”. If “environment” embraces the unthinkably vast numbers, complex relationships and inaccessibility of scientific knowledge, “umwelt” refers to the way trees and flowers and animals actually look, sound, smell, feel and taste to a particular person at a particular time. My umwelt is the way nature is for me.

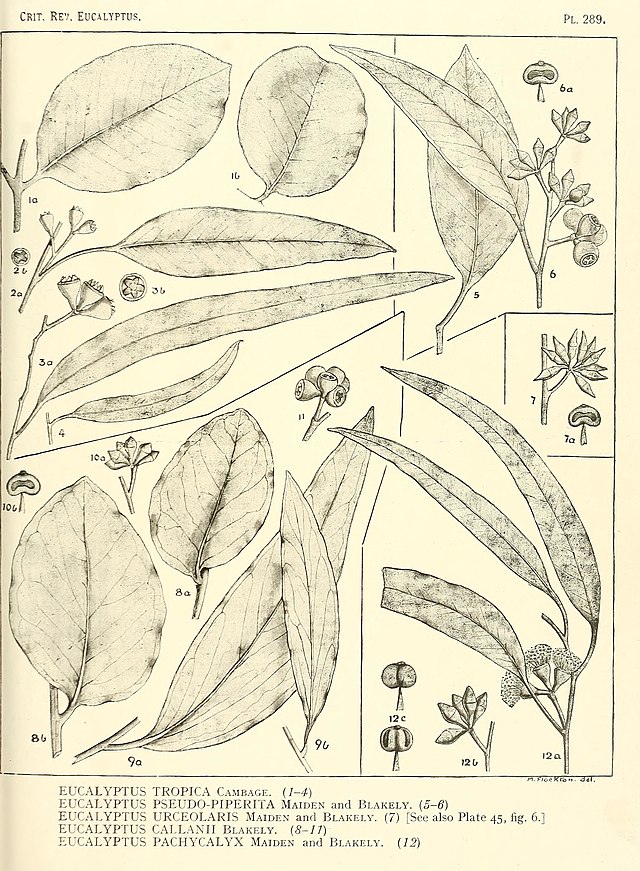

Yoon’s story begins with the beginning of taxonomy proper, the moment when the project of naming stepped back from the everyday terms of specific languages and localities — the multitude of independent umwelten — and aspired to global validity. Although most of us will have heard of Linnaeus (1707-1778), and associate him with authoritative two-part Latin names for plants and animals, I, for one, had not appreciated that the project presumed nature to be static and eternal, like a museum collection. Nor had I appreciated the presumption — sheer hubris, one might argue, of imposing names on plants seen only as isolated specimens — often dried and pressed on sheets of paper.

Only about a century later, Darwin cautiously proposed that nature changes over time, that species die out, evolve, divide, that new ones appear. Linnaean taxonomy could no longer claim either completeness or stability. It was further challenged, if perhaps less dramatically, by anthropological studies of many other, potentially competitive linguistic systems for ordering the natural world. Coming from all over the world, developed in most cases over longer times in much smaller geographical areas, many reflect rich understandings of the relationships among plants, animals, and people. Given such challenges, Linnaean taxonomy has done remarkably well — apparently because people everywhere see and hear and smell and taste in something like the same way. In fact systems of names, wherever they developed, almost all involve the same broad categories and relationships that Linnaeus recognised. Most even have systems involving two names — as Linnaeus did — designating a general and a more specific category.

The more dramatic challenge to Linnaeus’s systems was the need for taxonomy to recognise evolutionary relationships, genealogy. Yoon traces a series of steps from Linnaeus’s extraordinary naming of organisms based on his own perception — effectively his own umwelt — to truly arcane and time-consuming scientific methods of identification (e.g., DNA), followed by wholesale renaming and reordering of species based on known or presumed evolutionary relationships. The new methods don’t rely on direct human perception. The new names upset and alienate everyone — effectively leave “us” out, turn the whole project of naming and recognising into someone else’s concern.

For me, it was the most dramatic insight in a book containing many. I’ve long been drawn to the idea that human beings use language to create and sustain specific realities for themselves. But I certainly had not recognised taxonomy as such a superb example, possibly the all-time best example of how this actually happens, how such realities are created, sustained, contested and potentially lost.

The image is available at Wikimedia Commons.

View all my reviews [Goodreads]